This issue of The Erudite Magic Digest is going to be slightly more cerebral than most. I’ve been thinking more deeply about magic, and I want to share some of those insights with you here. Most of this is based on what I’ve been reading personally, even from outside of magic. In this newsletter, we’ll talk about what we can learn from Michelangelo, Al Baker, and Stewart James. I hope you get as much value from these lessons as I have studying these masters.

If this publication is new to you, welcome! My name is Jeff Kowalk, and this newsletter is an extension of Erudite Magic, my YouTube channel with weekly videos dedicated to sharing interesting magic books and related topics.

If you’re a returning reader or subscriber, welcome back! Thanks for your support through reading, sharing, and being an active member of the Erudite Magic community. I sincerely appreciate you.

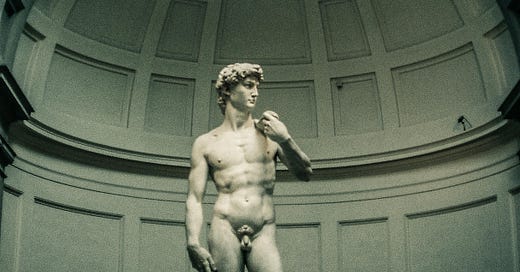

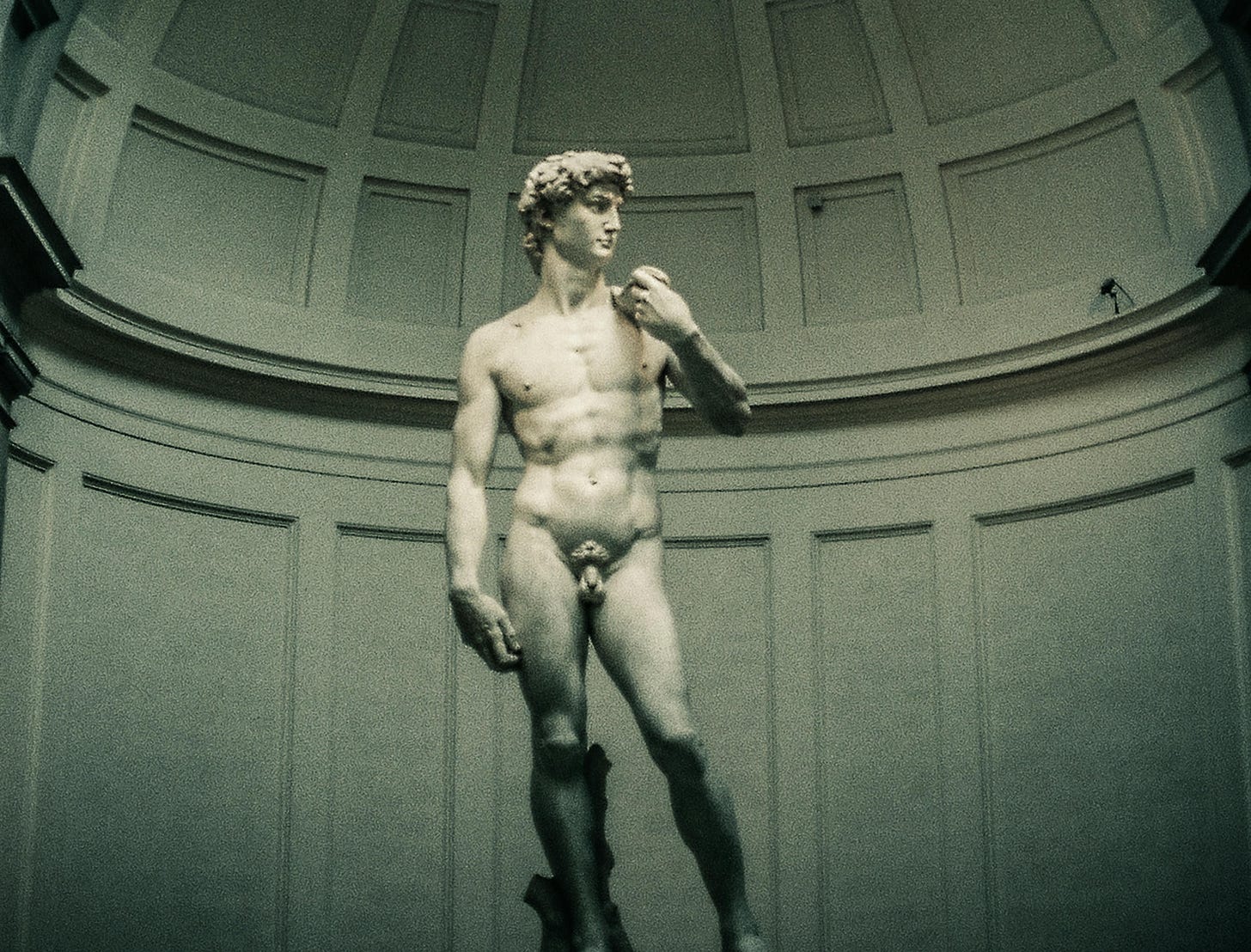

From marble to magic

Are you familiar with the story of Michelangelo and his David statue? Recently I learned that Michelangelo’s famous work was riddled with issues and famously flawed:

Flawed Material: The marble was of inferior quality, veined, and prone to cracking.

Abandoned by Others: Two sculptors had previously worked on it and deemed it unusable.

Awkward Dimensions: The block was unusually tall and narrow (over 17 feet long, but only 6 feet wide), limiting design options.

Weathered by Time: Left exposed for 25 years, it was further degraded by the elements and even some vandalism.

Despite these setbacks, Michelangelo transformed this damaged stone into one of the greatest artistic masterpieces in history.

At this point, you’re probably wondering, “how does this relate to magic?” As much as I’m not about to compare any magician I know to Michelangelo, I think the story is still relevant on a number of levels. Here are some of the lessons I think magicians can learn from this story:

1. Embrace Constraints as Opportunities

Michelangelo didn’t lament the block’s imperfections—he worked with them. Similarly, we often face limitations, whether it's performing in less-than-ideal settings, using subpar props, or dealing with a challenging audience. Instead of seeing these as obstacles, consider how they might inspire creativity and lead to innovative solutions.

2. Refine What Others Abandon

Two sculptors before Michelangelo abandoned the marble block, believing it was unworkable. Yet Michelangelo saw potential where others saw failure. As magicians, we might encounter effects or routines dismissed as outdated or flawed. With careful thought, we can transform these overlooked gems into something extraordinary.

3. Plan Meticulously, Then Execute Boldly

Michelangelo spent time studying the block’s flaws and carefully planning how to carve around them. Yet his chisel strokes, once started, were bold and confident. We, too, must balance preparation with execution. A well-rehearsed trick is only half the battle—it’s the presentation and scripting in performance that bring it to life.

4. Turn Weaknesses into Strengths

Michelangelo’s design for David was partially dictated by the block’s narrowness and previous cuts. He turned these constraints into a striking, elongated pose that conveys tension and readiness. In magic, a perceived weakness—such as limited props or angles—can be reframed into a feature of the trick that enhances its mystery.

5. Perseverance Pays Off

The block’s weathering, size, and flawed composition could have discouraged even the most skilled artist. Yet Michelangelo took the project head-on and spent over two years carving David. In magic, mastering a difficult sleight or perfecting a complex routine takes persistence, but the result is worth the effort.

6. The Final Result is What Matters

No one remembers the block’s flaws or the two sculptors who gave up on it. The world only sees the breathtaking David and remembers the artistry of Michelangelo. Similarly, your audience doesn’t care about the challenges you faced creating or performing an effect—they care about the final impact of your magic and your role in guiding them through the show.

By thinking like Michelangelo—seeing potential where others see problems and using every limitation to your advantage—you can elevate your magic to masterful levels. Remember, it’s not about having perfect materials or conditions; it’s about what you do with what you have.

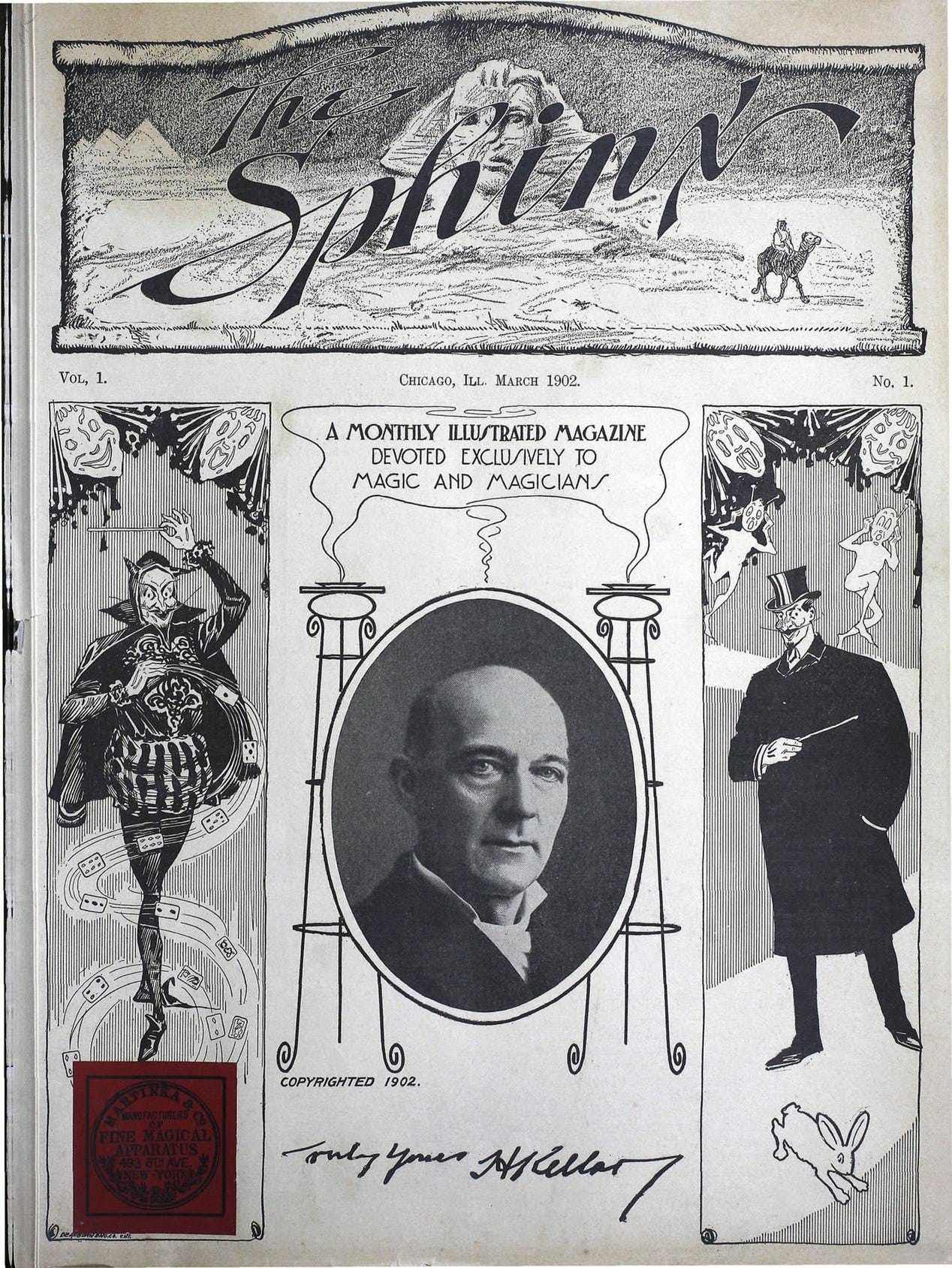

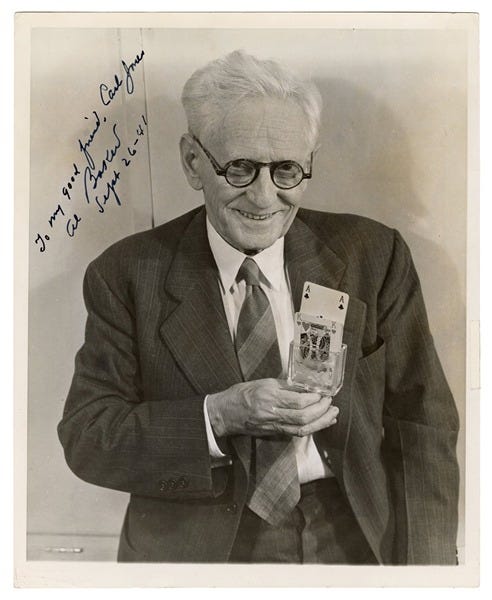

Al Baker never said that

Al Baker is often misquoted as having said, “Magicians stop thinking too soon.” While this pithy phrase captures an essential truth about the art of magic, it also reduces Baker’s actual insights into nothing more than a truism. Let’s revisit what he actually wrote—a passage that deserves its own fame for the nuanced understanding it reveals about magical thinking and the creative process.

“We must never forget that the details of presentation are what make a trick. And study and thought brings us those details. If you have a trick you like but never do because of some weak or unnatural or illogical part, don't lay it aside - just begin thinking. What I mean is thinking about that part. You will be surprised how a brilliant idea will crop up and you will be surprised even more that you hadn't thought of it before. The usual trouble is that we don't bother to think long enough or hard enough.”

- “What Makes a Trick” from The Sphinx, Volume 40, No. 1 (March 1941)

This passage, I think you’ll agree, is far more meaningful than the oversimplified version typically attributed to Baker. It’s true that we have all abandoned some effect or trick due to a weak aspect. But hopefully you’ve known the joy of applying the latter half of the quoted paragraph: thinking about the issue long enough to have a brilliant solution pop up based on the information you know.

Baker’s full quote reveals the limitations of the oversimplified phrase “Magicians stop thinking too soon.” His real argument emphasizes the importance of applying focused, deliberate thought to overcome challenges and craft effective solutions tailored to specific contexts—not just adding layers of complexity for the sake of it.

Baker’s advice to 'think long enough and hard enough' isn’t just theoretical. He applied this method himself, as he continues writing in the original article. He determined an elegant solution to the classic center tear problem (that the peek happens at exactly the wrong time - when everyone is staring you down). By addressing the inherent flaw of performing the peek when attention is highest, Baker transformed a weakness into a strength.

I’ve applied Baker’s advice myself in a special episode of Erudite Magic. I started with a John Bannon trick that wasn’t quite what I wanted, but by the end, I liked where it ended up. What do you think about the process?

What problems have you solved by thinking long and hard about them? And which tricks might you revisit now, armed with Baker’s advice to rethink the weak points?

So how do we make a trick more interesting?

Al Baker urged magicians to think deeply about their craft, solving weaknesses with focused creativity rather than abandoning tricks at the first sign of trouble.

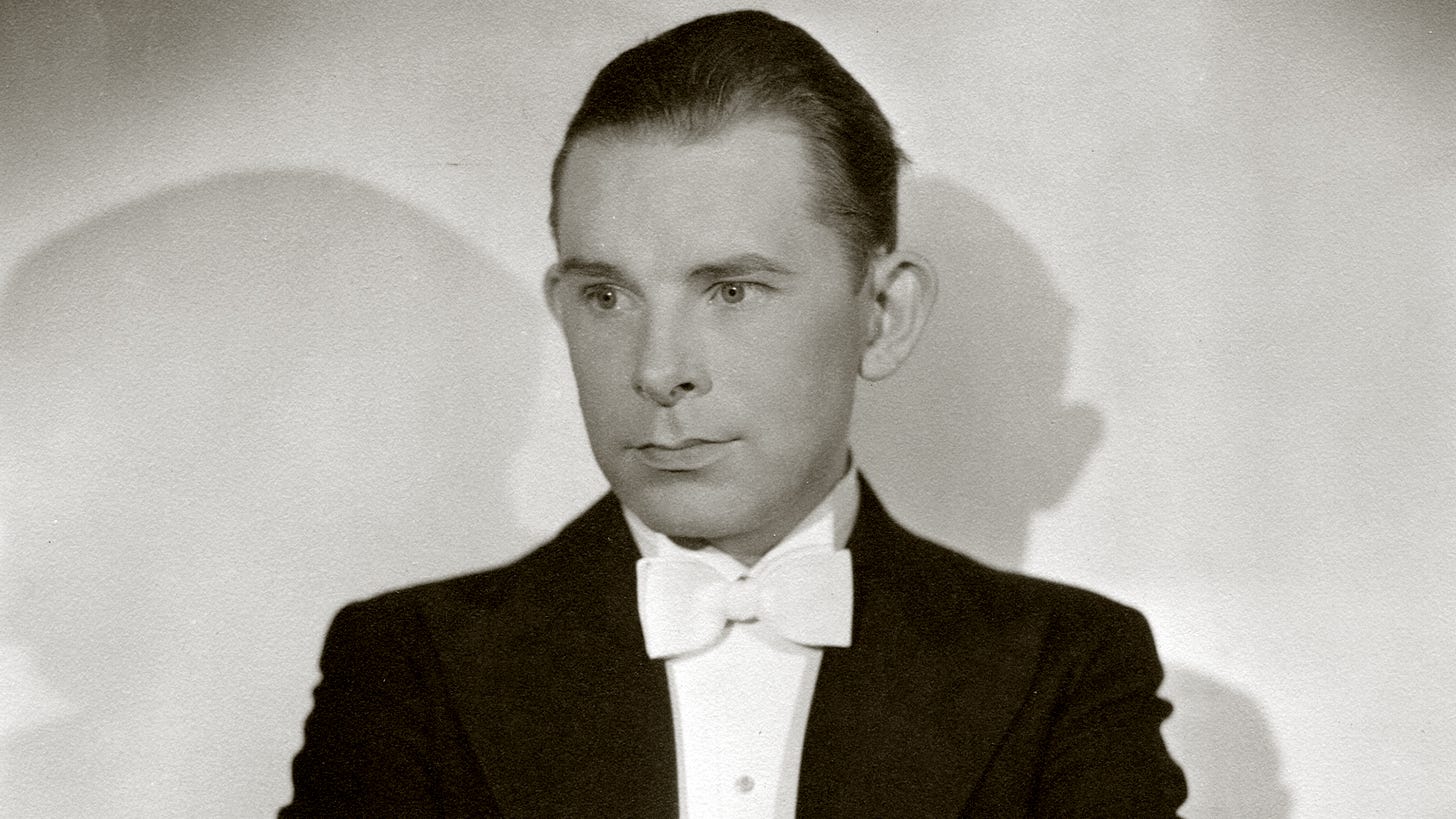

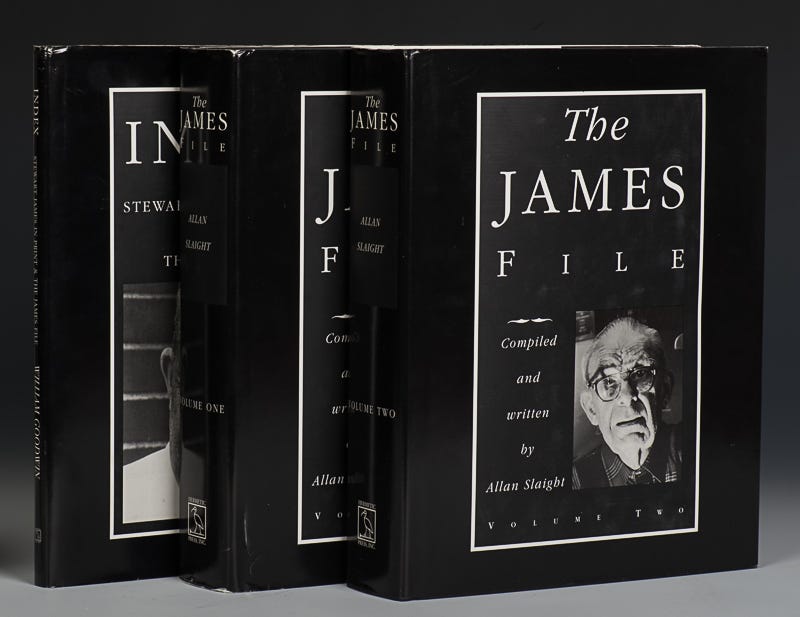

Stewart James took this idea of thinking deeply to an entirely different level (often to mixed, yet creative results), formulating intricate frameworks to guide his creative process. While Baker encouraged problem-solving for specific problems within a routine, James devised detailed tables to explore increasing audience appreciation and magical effect.

I believe James can help us as magicians solve some of the problems identified and discussed in Baker’s statements. Here’s an overview of James’s fascinating approach to structured creativity - let’s see how his methods can inspire us to think not just longer, but smarter:

As one of magic’s most prolific creators, James offers us a glimpse into his extraordinary thought process via a letter to his friend, Francis Haxton from December 1957. In this correspondence, James outlines his concept of Assumptive Trinities—a system of cataloging and analyzing ideas to enhance magical effects. It’s a confusing name, but don’t let it get you off track. This systematic approach allowed James to explore seemingly endless possibilities for a trick, unlocking new avenues of creativity and elevating our art of magic.

The Assumptive Trinities Framework

James describes his Assumptive Trinities as a tool to speed up research, experimentation, and creativity. These tables provide a structured way to explore the elements that shape the audience’s perception of a magical effect. The genius of it is that he breaks down [what could be] complex ideas into smaller, actionable components.

James identifies nine specific factors across these three dimensions:

Length or Space:

Distance between the spectator and the effect.

Distance between the performer and the effect.

Time taken to produce the effect.

Area or Size:

Visibility of props or actions.

Contrast between elements.

Naturalness or everyday familiarity of objects used.

Volume or Number:

Diversions leading up to the climax.

Number of objects involved.

Number of spectators directly engaged.

Applying the Table

James doesn’t force everything on the list into a trick. Instead, he suggests that we as performers should focus on the criteria most relevant to our specific routines and audiences. Using the example of the Brainwave Deck (as performed by Dunninger), he illustrates how manipulating one variable—distance—can significantly enhance audience appreciation. By presenting the trick with a remote participant, such as an authority figure hundreds of miles away, the impact of the effect is amplified beyond its standard close-up presentation.

This highlights the genius of James’s system: it isn’t a rigid checklist, but rather a flexible guide that encourages us to tailor our performances to maximize audience amazement. By analyzing variables systematically, we can elevate our routines from mere demonstrations to unforgettable miracles. His work invites all of us to think deeper, explore further, and push the boundaries of what magic can achieve.

A Hidden Gem Update

Last week, I shared a hidden gem from Asi Wind’s book, Repertoire. One of the Erudite Magic Digest readers (and close friend of mine), Adam Putnam, corresponded with me to remind me that there’s another trick in our libraries that has the finish my synergistic routine might have lacked. It reminded me that there are a lot of hidden gems hiding in plain sight, but I wanted to remind you about this one - it’s great!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Erudite Magic Digest to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.